Breaking

- MENU

Will 2019 see a third Knesset election? This question is going rounds in Israel as it faces the second parliamentary election on 17 September and given the fractured verdict in the 9 April vote, one cannot be definite about anything. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's strategy of advancing the 21st Knesset election, which was due only this November, boomeranged. Both to tide over the crisis over the drafting of the ultra-orthodox Haredi population and to shore up his authority, he pushed it forward to April. As the Israelis were watching the cliff-hanger exit poll, Netanyahu was quick and even brash, in claiming a premature victory.

The Likud headed by him secured the same number of seats—35 in the 120-member house—like its immediate challenger Blue and White, led by former general Benny Gantz. The difference between the two parties was 14,489 out of 4.34 million voters. This small difference resulted in Netanyahu being asked to form the government and he almost cobbled a narrow Right-Religious coalition, but he fell short by one seat to ensure a simple majority of 61 seats.

With five seats, Avigdor Lieberman, a one-time aide of Netanyahu—became the potential kingmaker. Yisrael Beiteinu headed by the former Defense Minister was not prepared to join the government without the Haredi population doing military service. When Lieberman stood his grounds, Netanyahu could not form the government within the legally stipulated time. To prevent others, both within and outside the Likud, from staking claims, Netanyahu settled for dissolving the Knesset, forcing a second election within six months.

This is the first time in Israel's history re-election became necessary because a new government could not be formed after the popular vote. Despite all fractions and divisions, Israel always had an elected- government. When political stalemate continued after the 1984 and 1988 elections, both Likud and Labour Party came together and formed a national unity government. This did not happen after the April election.

While it is too early and hazardous to predict the outcome of the 17 September election, one cannot ignore certain harsh realities. The ruling Likud party is in a deep crisis over its future. Since the pre-state years, the party had seen only four leaders, namely, Menachem Begin, Yitzhak Shamir, Ariel Sharon and Netanyahu and the Labour Party on the other had over a dozen during the same period. While there are a few contenders for the Likud leadership, all of them lack Netanyahu's national and international stature and the party would be muddling along for quite some time after Bibi, as the prime minister is fondly called.

Two, Netanyahu's troubles with the law is far from over and the Attorney General has set 2 October for pre-indictment hearing, just two weeks after the Knesset election, over bribery charges. This means that Netanyahu cannot bring in a legislation that would prevent the filing of charges against an incumbent prime minister. Thus, even if Likud emerges as the largest party, the chances of Netanyahu heading the next government gets slimmer.

Three, ever since he entered parliament in 1988, Netanyahu had dominated the Israeli political landscape. Even in his caretaking capacity, on 16 July he overtook David Ben-Gurion and became the longest-serving prime minister of the country. At the same time, there is noticeable fatigue even among the right-wing voters about Netanyahu's three-decade-long political career. There is a genuine yearning for change, even if the outcome is less clear and more uncertain. This might work against Netanyahu who mastered political survival as an art.

Four, part of Netanyahu's domestic popularity is also due to his proximity with President Donald Trump and his success in securing a spate of diplomatic victories. The American recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital, the shifting of American Embassy out of Tel Aviv and recognition of the Golan Heights as an Israeli territory are Netanyahu’s remarkable achievements. These moves are controversial and much of the international community has not accepted them as legitimate, but within the Israeli domestic contest, they are Netanyahu's diplomatic accomplishments. At the same time, are they a result of Netanyahu-Trump personal bonhomie or an Israeli-US interest convergence? Will President Trump be showering similar concessions, if the next Israeli leader is not Netanyahu?

If one considers these, the forthcoming Knesset election faces more questions than answers and would be the most crucial one in recent times.

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

Professor P R Kumaraswamy is Honorary Director of MEI@ND.

THE WAR IS OVER! President Donald Trump declared loudly and repeatedly, on Air Force One en rou.....

A bizarre adventure that went terribly wrong. The strategic benefits of the September 9 Israeli atta.....

The Ministry of External Affairs recently announced that Paramita Tripathi, from the 2001 batch of t.....

How many Indians are there in the GCC countries? For a long time, this was largely resigned to specu.....

As a growing number of Western states are moving towards recognising the Palestinian State, a powerf.....

As human sufferings in the Gaza Strip show no signs of an early end, India is doggedly committed to .....

Like much of the international community, India was quick to embrace the goals and objectives of the.....

Realpolitik. Pragmatism. Making a virtue out of necessity. Regardless of how one looks at it, the Is.....

All going well—which is a big IF in the ever-turbulent Middle East—the Gaza ceasefire sh.....

Described as a ‘pre-emptive’ strike, Operation Rising Lion is the first armed conflict I.....

The election of Pope Leo LIV as the successor to Francis, with the participation of a hand full of c.....

As the fragile ceasefire came into effect on May 10, Türkiye became the focus of the ire of sev.....

It was the first Friday after the Pahalgam terror attack. Along with a group of students of Jawaharl.....

Vanishing. This is the frequent and inevitable expression when discussing the Christians of the Midd.....

THE PAHALGAM TERRORIST attack has highlighted the cleavages in the Middle East on terrorism. In.....

When peace is viewed as ‘surrender’, there is little one can accomplish. Without an effe.....

The magnitude of the missile attack on Israel carried out by Iran in the early hours of Sunday was u.....

While the details are still emerging, the Hamas attacks from the Gaza Strip on Saturday were well pl.....

The Libyan controversy reminds us of the more significant problem facing Israel. While the scale and.....

64-0! It should be an impressive vote in any country, especially in Israel, where a simple parliamen.....

King Bibi is back! After one year in the Opposition, Benjamin Netanyahu, a close friend of Prime Min.....

Political instability is an integral and inseparable part of Israel’s landscape. For the fifth.....

Even by the Israeli standard of coalition fragility, the Bennett-Lapid government, which completed o.....

Soon to enter its fourth month, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made irreversible damages to glo.....

The visit of Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett to India scheduled for last week had to be cance.....

The drone attack on Abu Dhabi on Monday (January 17) by the Houthi rebels marks a major escalation o.....

Of late, Israel-Iran shadow-boxing has been getting ominous. If Israel’s diplomatic offensive .....

In early November, Moscow hosted Mohammed Dahlan, a former right-hand man of Palestinian leader Yass.....

Nearly three decades after Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao broke from the past and normalised relat.....

Earlier it was Pakistan and now China. So whatever India does and does not do externally has to be l.....

In several ways, the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan can be a game-changer in India’s worldvie.....

The Taliban takeover and its fallout exposed the limited diplomatic space for India in its immediate.....

Given the travel restrictions, local lockdown and sluggish economic revival, that over three lakh pe.....

Since 2005, some critical decisions over Iran have been taken by the MEA’s US Division. So que.....

“Bibi dethroned”. This is the expression used in the Israeli media to describe the forma.....

Despite having a woman prime minister in Golda Meir, female political representation in Israel has n.....

The most interesting aspect of the new Bennett-Lapid government in Israel is the emergence of Mansou.....

When it comes to mediating international crises, India’s track record is a mixed bag. In recen.....

Going by the Israeli media, it is clear that the arm-twisting by the Biden Administration forced the.....

Indeed, Hamas is better placed today than it was in January 2006 and the current round of violence i.....

While the international community wants de-escalation and an early end to the conflict, the chances .....

Ending the past silence, US President Joe Biden marked the Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day of Apri.....

The visit of Foreign Minister of Bahrain Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani to India during 6-8 April r.....

By posthumously bestowing the Gandhi Peace Prize for 2019 upon Sultan Qaboos of Oman, New Delhi seek.....

Much to the displeasure and discomfort of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (more widely known .....

The nomination of Robert Malley, a veteran hand in Washington policy circles, as the Special Envoy f.....

The two-day visit of External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar to the United Arab Emirates last week is.....

United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) decision to normalise relations with Israel is the most dramatic e.....

Declaring victory moments after the polling ends has become the hallmark of Benjamin Netanyahu; and .....

Israel went to polls for the 23rd Knesset on 2nd March. The third parliamentary elections within one.....

With possible removal from office hanging over their heads, US President Donald Trump and Israeli Pr.....

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s sudden and unexpected announcement regarding Israeli settl.....

US President Donald Trump’s decision on imposing sanctions on Turkey has rocked the ever-turbu.....

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s two-day visit to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia this week highligh.....

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's reported decision to postpone a planned visit to Turkey comes a c.....

With the sole and notable exception of Pakistan, India's relations with the wider Islamic world .....

For a long time, India’s relationship with its extended neighbourhood in the Persian Gulf was .....

The Israeli legislative or Knesset election last week has turned out to be a rerun of the 9 April on.....

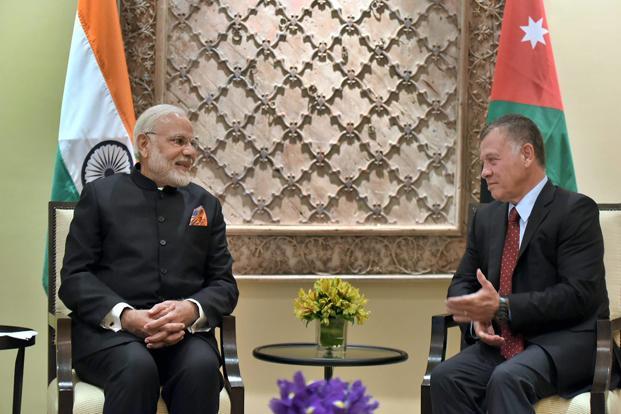

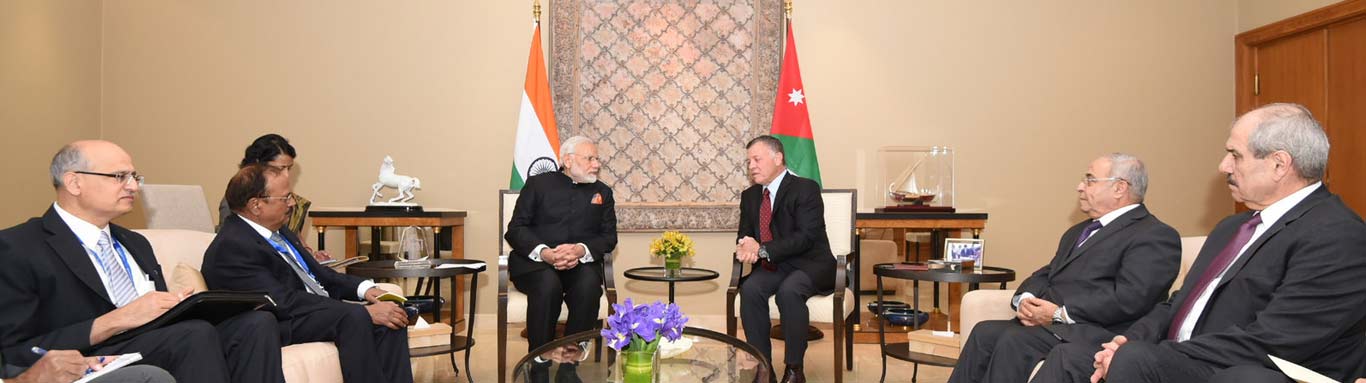

When he called Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to congratulate on his re-election with a landsli.....

The resounding re-election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is a blessing for India's relat.....

Iran is back in the news and for all the wrong reasons. It has been the unnecessary third .....

During the close to a century of its existence, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has been, as former .....

In their eagerness to focus on and flag the de-hyphenation of the traditional Israel-Palestinian bin.....

In the closely scrutinised India-Israel relationship, there is little in the public domain that rema.....

You know what, it will go to the dustbin’ my articulate friend was blunt, brutal but.....

Balfour Declaration, A Century Later If one were to make a list of the most influential.....

Professor Bernard Lewis—a towering personality on the Middle Eastern academic landscape—.....

B orn in Poland on 2 August 1923, Szymon Persk who later Hebraised his name as Shimon Peres was the leader.....

W hat What began as a protest by a marginalized vegetable vendor in Sidi Bouzid in Tunisia soon spread lik.....