Breaking

- MENU

Declaring victory moments after the polling ends has become the hallmark of Benjamin Netanyahu; and for the third time, this strategy did not work. He got the highest number of seats for the Likud since taking over its reigns in 1992, but they are still insufficient to cross the line. Israelis, who went to the poll for the third time within a year, delivered an inconclusive verdict, and a challenge to the politicians.

The facts first! Israel has always witnessed a high voter turnout by any standards. It was 68.41 percent in April, and 69.83 percent in September 2020, and was 71.52 percent this March. The results of the 2 March election to the 120-member Knesset are as follows. Likud-36; Blue and White-33; Arab Joint List-15; Shas-9; United Torah Judaism (UTJ)-7; Yisrael Beiteinu-7; Labour-Gesher-Meretz-7; Yamina-6. In terms of blocs, the Right-Religious combine has 58 seats while the Centre-Left bloc has 55 seats; with seven seats Yisrael Beiteinu, led by Avigdor Lieber, a one-time ally of Netanyahu, is angling to be the kingmaker.

Who could form the next government, and with whom? There a few options, and each one as problematic as the other.

Likud-led government under Netanyahu: Netanyahu, who has been dominating the Israeli political landscape ever since he took over the reins of the Likud in 1992, has no plans to go home quietly. The prospect of appearing in a Jerusalem court on 17 March on charges of corruption has not lessened his appetite. In recent months he even sought, unsuccessfully though, parliamentary immunity. While former President Moshe Katsav and former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert were convicted, Netanyahu is the first serving prime minister to be indicted, and to appear in a court. His victory claims moments after polls ended was a strategy to create a buzz that he would stay on office, and delay the judicial process.

Netanyahu is no ordinary leader, and he is now the longest-serving prime minister in Israel's history and also is heading the longest caretaker government since December 2018. Under him, the Israeli economy has flourished, and its political fortunes expanded. Netanyahu was partly helped by US President Donald Trump, and his controversial policies; for example, declaring Jerusalem as Israel's capital; Golan Heights as an Israeli territory, and settlements in the occupied territories as legal. These American moves are not in sync with the international opinion, but they boosted Netanyahu’s standing within the country and presented him as someone who enjoys closer ties with Washington. He could deliver what others only imagined or whispered in private.

Netanyahu still needs three more seats to cross the magic number of 61 for a simple majority. During the runup to the election, and after, he was hinting at, and banking on a possible defection from the Blue and White or factions which make up that bloc led by former Army Chief Benny Gantz. There are murmurs within Blue and White but no open rebellion, or at least not yet.

Netanyahu's second option is to entice his former aide Lieberman to join his coalition. Going by the public spats between the two, an Israeli-Palestinian peace looks more likely than a Netanyahu-Lieberman reconciliation. Had it been possible, there was no need for the second, let alone third, election within the year. The aide-turned-nemesis is determined to prevent an 'indicted person' heading the next government and there are no signs of Lieberman’s compromise.

Likud-led government but without Netanyahu: This could easily resolve the stalemate and would enable even Lieberman to join hands with a Likud-led government with a working coalition of 65 MKs. This presupposes Netanyahu resigning from Likud leadership, either before he faces the court on 17th or afterwards.

Netanyahu’s determination to stay in office was largely responsible for the Israelis going to polls thrice within a year, but he still enjoys the overwhelming support within the Likud. Since the late 1930s, the party (and its predecessors) had only seen four leaders, namely, Menachem Begin, Yitzhak Shamir, Ariel Sharon, and Netanyahu. As happens not most political parties, there are no towering figures within Likud, and Netanyahu's departure would plunge the party into a leadership crisis, and even an implosion. The proverbial there-is-no-alternative or TINA factor works in his favour. The future of the Likud is bleak if Netanyahu were to leave now. The same holds for the right and religious parties who are clinging on to him. Having tied themselves to Netanyahu, they would also lose, if Likud were to replace Netanyahu with a lesser-known figure.

Likud-Blue and White Unity Government: This has been widely suggested, and Israel did have unity governments when 1984, and 1988 elections presented a stalemate. This compelled Likud and to agree for a rotational arrangement, and govern the country until 1990 when Labour bolted out due to differences over the peace process. Indeed, since the April 2019 election, President Reuven Rivlin has been nudging Likud and Blue and White to find ways to cooperate but in vain. As a former Likudnik Rivlin was not enamoured by Netanyahu, and often expressed his differences over a host of issues, but his ideas for a unity government have not materialized. The thorny issue is not a unity government per se but who would be the prime minister. The opposition is not ready to accept an indicted person as the leader of the coalition, and Netanyahu is not yet prepared to leave. Without Netanyahu, the religious parties will not join the Blue and White to form a unity government.

Blue and White government without the Right-Religious bloc: With 62 seats at his disposal comprising of Blue and White, Labour bloc, Arab List, and Lieberman, Gantz could form a government with a wafer-thin majority. The Arab List has emerged as the third-largest bloc in the March election, and internal unity and pre-election arrangements led to the Arab parties securing the highest number of seats in Israel’s history. However, a government with the full participation of the Arabs may be ideal but unrealistic. Balad within the Arab List, for example, is anti-Zionist, and an Israeli government that is dependent upon the Arab parties does not look promising; at least, not today.

Blue and White with religious parties: The defection of the National Religious Parties facilitated the first Likud-led government in 1977 under Menachem Begin. From then on, the religious parties have been siding with the Likud. If Gantz manages to break this cycle, the chances of forming a government increase. With 16 seats, they could give both legitimacy and stability, but this would keep Lieberman away, and even the Labour-led bloc, especially the Meretz, may not be enamoured by religious parties back at the helms. Without Labour bloc and Lieberman, Gantz will have only 49 seats, falling 12 short of a working majority.

Minority government under Blue and White: Realizing the odds, Gantz might consider a minority government comprising of Blue and White, Lieberman, and Labour bloc that would give him a coalition of 47 MKs with the outside support of the Arab parties. Under this, Arabs would be part of the bloc majority but not of the ruling coalition. The figment of Arab non-inclusion might reduce the critics, and might be more palatable. In the 1990s, the government of Yitzhak Rabin survived with the outside support of the Arab parties, who had five seats and this enabled him to pursue the Oslo process with the Palestinians. The semi-participation of the Arabs would moderate both sides; legitimacy of the Arabs, and their integration with the Israeli political establishment. The fractured verdict does not give sufficient space for radical changes but could compel both sides to move towards accommodation; gingerly, and not radically.

The flip side of this arrangement is not Arab exclusion but Lieberman's inclusion, which will keep the religious parties away. Given the growing segment of the religious population, an Israeli government without the participation of religious parties would not survive for long.

The impossible option: How about a government that comprises only Blue and White and the Labour bloc but with the outside support of Arabs and Lieberman? This would mean Gantz having a 40-member coalition with 22 MKs giving outside support! Excluding the Arabs would diminish anti-Zionist charge against the government, and not including Lieberman will open doors for the religious parties. Lieberman's shopping list is directed at increased pension benefits, Haredi conscription, and limiting the powers of the religious establishment in civilian matters. He is less hostile to the Arabs, and not long ago, his main ire was directed at the Arabs and now this had moved towards the direction of Netanyahu. Likewise, the Arabs are also slowly moving towards endorsing the former general for the premiership.

A minority government with the outside support of Arabs and Lieberman conveys a strong message to religious parties: Netanyahu is not a viable option. Either they join the Gantz-led government or stay in opposition ranks until the next election. Religious parties, by nature, cannot remain out of office for long. Their constituency needs deliverables, which can only happen if they are part of the ruling coalition. Except for a brief period in the 1990s, religious parties were always part of the government. If Blue and White-led government manages stability, and addresses some of the thorny domestic issues, the religious bloc will have to reconsider and switch sides. If and when this happens, the religious parties would be less opposed to the formal inclusion of the Arab List than others. This would mean, while seeking the outside support of Lieberman, Gantz will have to look a face-saving formula that would enable Yisrael Beiteinu and religious parties to tolerate each other; perhaps a compulsory national service for the Haredi, as opposed to conscription, might work.

Impossible, yes! The Holy L, and if full of miracles. Why not a Gantz-led minority government with the outside support of Arabs and Lieberman (and perhaps religious parties at a later date)? Will 40 be bigger than 58?

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

Professor P R Kumaraswamy is Honorary Director of MEI@ND.

When peace is viewed as ‘surrender’, there is little one can accomplish. Without an effe.....

The magnitude of the missile attack on Israel carried out by Iran in the early hours of Sunday was u.....

While the details are still emerging, the Hamas attacks from the Gaza Strip on Saturday were well pl.....

The Libyan controversy reminds us of the more significant problem facing Israel. While the scale and.....

64-0! It should be an impressive vote in any country, especially in Israel, where a simple parliamen.....

King Bibi is back! After one year in the Opposition, Benjamin Netanyahu, a close friend of Prime Min.....

Political instability is an integral and inseparable part of Israel’s landscape. For the fifth.....

Even by the Israeli standard of coalition fragility, the Bennett-Lapid government, which completed o.....

Soon to enter its fourth month, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made irreversible damages to glo.....

The visit of Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett to India scheduled for last week had to be cance.....

The drone attack on Abu Dhabi on Monday (January 17) by the Houthi rebels marks a major escalation o.....

Of late, Israel-Iran shadow-boxing has been getting ominous. If Israel’s diplomatic offensive .....

In early November, Moscow hosted Mohammed Dahlan, a former right-hand man of Palestinian leader Yass.....

Nearly three decades after Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao broke from the past and normalised relat.....

Earlier it was Pakistan and now China. So whatever India does and does not do externally has to be l.....

In several ways, the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan can be a game-changer in India’s worldvie.....

The Taliban takeover and its fallout exposed the limited diplomatic space for India in its immediate.....

Given the travel restrictions, local lockdown and sluggish economic revival, that over three lakh pe.....

Since 2005, some critical decisions over Iran have been taken by the MEA’s US Division. So que.....

“Bibi dethroned”. This is the expression used in the Israeli media to describe the forma.....

Despite having a woman prime minister in Golda Meir, female political representation in Israel has n.....

The most interesting aspect of the new Bennett-Lapid government in Israel is the emergence of Mansou.....

When it comes to mediating international crises, India’s track record is a mixed bag. In recen.....

Going by the Israeli media, it is clear that the arm-twisting by the Biden Administration forced the.....

Indeed, Hamas is better placed today than it was in January 2006 and the current round of violence i.....

While the international community wants de-escalation and an early end to the conflict, the chances .....

Ending the past silence, US President Joe Biden marked the Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day of Apri.....

The visit of Foreign Minister of Bahrain Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani to India during 6-8 April r.....

By posthumously bestowing the Gandhi Peace Prize for 2019 upon Sultan Qaboos of Oman, New Delhi seek.....

Much to the displeasure and discomfort of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (more widely known .....

The nomination of Robert Malley, a veteran hand in Washington policy circles, as the Special Envoy f.....

The two-day visit of External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar to the United Arab Emirates last week is.....

United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) decision to normalise relations with Israel is the most dramatic e.....

Israel went to polls for the 23rd Knesset on 2nd March. The third parliamentary elections within one.....

With possible removal from office hanging over their heads, US President Donald Trump and Israeli Pr.....

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s sudden and unexpected announcement regarding Israeli settl.....

US President Donald Trump’s decision on imposing sanctions on Turkey has rocked the ever-turbu.....

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s two-day visit to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia this week highligh.....

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's reported decision to postpone a planned visit to Turkey comes a c.....

With the sole and notable exception of Pakistan, India's relations with the wider Islamic world .....

For a long time, India’s relationship with its extended neighbourhood in the Persian Gulf was .....

The Israeli legislative or Knesset election last week has turned out to be a rerun of the 9 April on.....

Will 2019 see a third Knesset election? This question is going rounds in Israel as it faces the seco.....

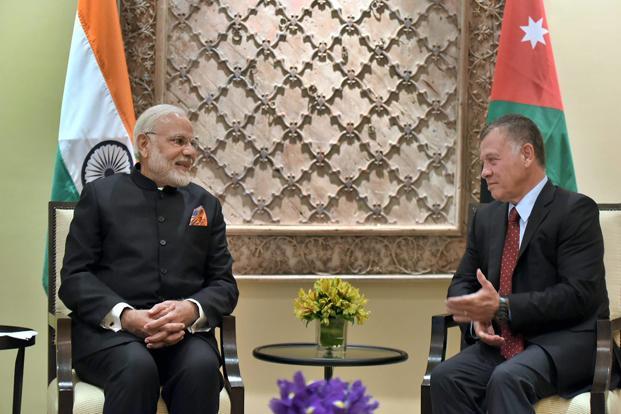

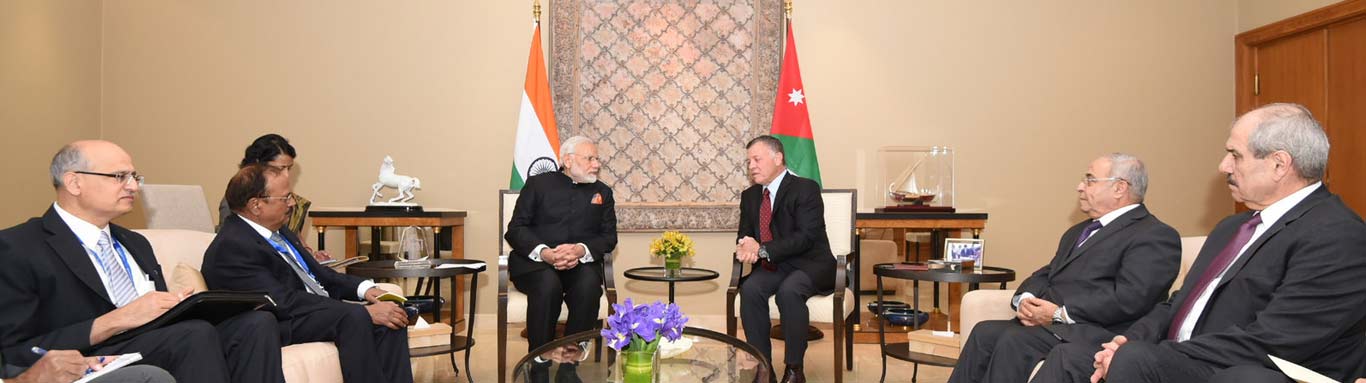

When he called Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to congratulate on his re-election with a landsli.....

The resounding re-election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is a blessing for India's relat.....

Iran is back in the news and for all the wrong reasons. It has been the unnecessary third .....

During the close to a century of its existence, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has been, as former .....

In their eagerness to focus on and flag the de-hyphenation of the traditional Israel-Palestinian bin.....

In the closely scrutinised India-Israel relationship, there is little in the public domain that rema.....

You know what, it will go to the dustbin’ my articulate friend was blunt, brutal but.....

Balfour Declaration, A Century Later If one were to make a list of the most influential.....

Professor Bernard Lewis—a towering personality on the Middle Eastern academic landscape—.....

B orn in Poland on 2 August 1923, Szymon Persk who later Hebraised his name as Shimon Peres was the leader.....

W hat What began as a protest by a marginalized vegetable vendor in Sidi Bouzid in Tunisia soon spread lik.....