Breaking

- MENU

Since 2005, some critical decisions over Iran have been taken by the MEA’s US Division. So questions arise if Jaishankar’s recent brief halt in Tehran was coordinated with Washington

While the Indian government described it as a ‘technical halt’, many eyebrows were raised over the brief stopover of External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar in Tehran on July 7. The ‘diplomatic surprise’ took place amidst the major Cabinet reshuffle in New Delhi. The official announcement before Jaishankar’s Moscow visit did not indicate a detour to Iran. For his part, Jaishankar tweeted: “Thank President-elect Ebrahim Raisi for his gracious welcome. Handed over a personal message from PM… Appreciate his warm sentiments for India. Deeply value his strong commitment to strengthen our bilateral ties and expand cooperation on regional and global issues.”

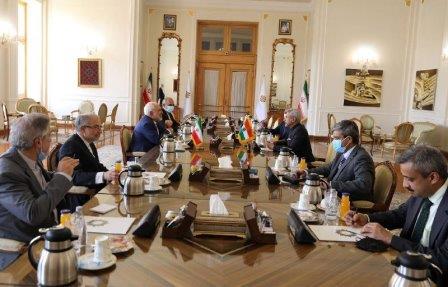

It is obvious that the ‘technical halt’ was pre-planned and choreographed. The few hours of stay in Tehran was marked by the EAM’s meeting with President-elect Raisi and his Iranian counterpart Dr Javid Zarif. The meeting with the latter is a mere formality as he would be leaving office when Raisi becomes president. The MEA official spokesperson listed out issues discussed between the two sides: regional and global issues, Afghanistan, the Vienna negotiations over the resumption of the nuclear deal abandoned by former US President Donald Trump, the North-South Transport Corridor and Chabahar port. Another twist came a few days later when India announced its acceptance of the invitation for the inauguration of Raisi’s presidency on August 3.

Iran has been the most challenging aspect of India’s foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. New Delhi has been unable to synchronise its overlapping and conflictual interests vis-a-vis Tehran. At one level, it has been seeking closer ties with the dominant country in the Persian Gulf region that also has considerable oil and gas reserves vital for India’s economic growth. In addition, interest convergence over Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia added a strategic dimension to the bilateral relations.

At the same time, since the Islamic revolution, Iran has been pursuing a belligerent, and some might say hegemonic policy, vis-a-vis its Arab neighbours. Opposed to external powers—including India—playing any role in the region, Tehran sees the Persian Gulf as its exclusive sphere of influence. Over time, the Iran-Saudi rivalry and competition transformed into a sectarian conflict between the two branches of Islam, Sunni and Shia. Tehran’s policy towards the US and Israel also complicated India’s options.

If these challenges are not sufficient, the Ministry of External Affairs has also created operational complications. The Islamic Republic does not fall under the West Asia and North African (WANA) Division of the Ministry but is part of the PAI Division comprising Pakistan and Afghanistan. This means the Gulf Division, which deals with the countries along the Persian Gulf, does not include Iran. Ironically, when Iran is the major preoccupation of the Gulf Arab states and their political stability, India’s Gulf policy is formulated without any inputs from or on Iran. Clubbing Iran with Pakistan made sense during the Cold War when both were close allies or when Pakistan was India’s dominant foreign policy preoccupation. But to perpetuate this when India is seeking closer ties with Gulf Arab countries? The much-publicised restructuring undertaken in 2020 did not address India’s Persian puzzle in the Gulf.

If keeping Iran out of the internal deliberations on the Gulf is not enough, India found a new hurdle. Since early 2005, some of the critical decisions concerning Iran have been taken not by the PAI Division but by the US Division as New Delhi tries to ‘coordinate’ and synchronise its Iran policy with Washington. Whether it was the vote on the Iranian nuclear programme in IAEA in 2005 or stopping oil imports from Iran, the US Division had a pre-eminent role. Therefore, questions arise if Jaishankar’s brief halt in Tehran and the meeting with President-elect Raisi were coordinated with Washington.

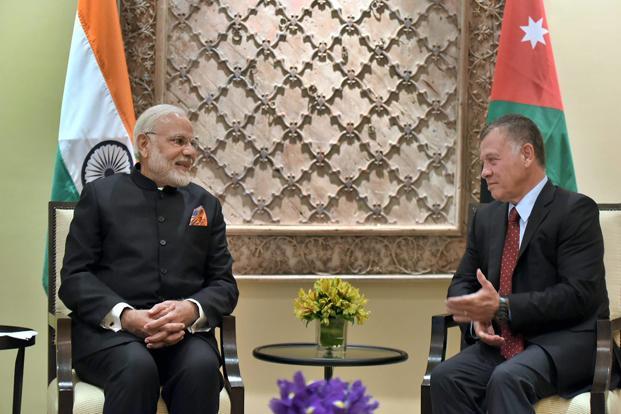

Two, while several Western nations were reluctant, on June 20, the day after Raisi was declared the winner in the presidential election, PM Narendra Modi tweeted his congratulatory message and expressed his desire to “working with him to further strengthen the warm ties.” This would add a twist with the US, especially the liberal section of the Democrats committed to human rights. Indeed, Raisi becomes the first incoming president of Iran under US sanctions (imposed in November 2019) over his alleged role in the systematic abuse and violation of human rights. So any Indian move towards Iran under Raisi will add more spice to Modi-Biden relations.

Three, for its part, Iran has outmanoeuvred India and is perhaps seeking a wedge between New Delhi and its Gulf Arab partners, especially Saudi Arabia. By bestowing on Jaishankar the honour of being the first foreign dignitary to meet the incoming President, Tehran might use the meeting in its relations with its other friends like Russia and China. Thus, Jaishankar’s brief meeting with Raisi days before the latter’s inauguration opens a new and interesting chapter for India and its ability to manage conflicting pulls over its Gulf policy.

Note: This article was originally published in The New India Express on 14 July 2021 and has been reproduced with the permission of the author. Web Link

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

Professor P R Kumaraswamy is Honorary Director of MEI@ND.

When peace is viewed as ‘surrender’, there is little one can accomplish. Without an effe.....

The magnitude of the missile attack on Israel carried out by Iran in the early hours of Sunday was u.....

While the details are still emerging, the Hamas attacks from the Gaza Strip on Saturday were well pl.....

The Libyan controversy reminds us of the more significant problem facing Israel. While the scale and.....

64-0! It should be an impressive vote in any country, especially in Israel, where a simple parliamen.....

King Bibi is back! After one year in the Opposition, Benjamin Netanyahu, a close friend of Prime Min.....

Political instability is an integral and inseparable part of Israel’s landscape. For the fifth.....

Even by the Israeli standard of coalition fragility, the Bennett-Lapid government, which completed o.....

Soon to enter its fourth month, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made irreversible damages to glo.....

The visit of Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett to India scheduled for last week had to be cance.....

The drone attack on Abu Dhabi on Monday (January 17) by the Houthi rebels marks a major escalation o.....

Of late, Israel-Iran shadow-boxing has been getting ominous. If Israel’s diplomatic offensive .....

In early November, Moscow hosted Mohammed Dahlan, a former right-hand man of Palestinian leader Yass.....

Nearly three decades after Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao broke from the past and normalised relat.....

Earlier it was Pakistan and now China. So whatever India does and does not do externally has to be l.....

In several ways, the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan can be a game-changer in India’s worldvie.....

The Taliban takeover and its fallout exposed the limited diplomatic space for India in its immediate.....

Given the travel restrictions, local lockdown and sluggish economic revival, that over three lakh pe.....

“Bibi dethroned”. This is the expression used in the Israeli media to describe the forma.....

Despite having a woman prime minister in Golda Meir, female political representation in Israel has n.....

The most interesting aspect of the new Bennett-Lapid government in Israel is the emergence of Mansou.....

When it comes to mediating international crises, India’s track record is a mixed bag. In recen.....

Going by the Israeli media, it is clear that the arm-twisting by the Biden Administration forced the.....

Indeed, Hamas is better placed today than it was in January 2006 and the current round of violence i.....

While the international community wants de-escalation and an early end to the conflict, the chances .....

Ending the past silence, US President Joe Biden marked the Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day of Apri.....

The visit of Foreign Minister of Bahrain Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani to India during 6-8 April r.....

By posthumously bestowing the Gandhi Peace Prize for 2019 upon Sultan Qaboos of Oman, New Delhi seek.....

Much to the displeasure and discomfort of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (more widely known .....

The nomination of Robert Malley, a veteran hand in Washington policy circles, as the Special Envoy f.....

The two-day visit of External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar to the United Arab Emirates last week is.....

United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) decision to normalise relations with Israel is the most dramatic e.....

Declaring victory moments after the polling ends has become the hallmark of Benjamin Netanyahu; and .....

Israel went to polls for the 23rd Knesset on 2nd March. The third parliamentary elections within one.....

With possible removal from office hanging over their heads, US President Donald Trump and Israeli Pr.....

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s sudden and unexpected announcement regarding Israeli settl.....

US President Donald Trump’s decision on imposing sanctions on Turkey has rocked the ever-turbu.....

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s two-day visit to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia this week highligh.....

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's reported decision to postpone a planned visit to Turkey comes a c.....

With the sole and notable exception of Pakistan, India's relations with the wider Islamic world .....

For a long time, India’s relationship with its extended neighbourhood in the Persian Gulf was .....

The Israeli legislative or Knesset election last week has turned out to be a rerun of the 9 April on.....

Will 2019 see a third Knesset election? This question is going rounds in Israel as it faces the seco.....

When he called Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to congratulate on his re-election with a landsli.....

The resounding re-election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is a blessing for India's relat.....

Iran is back in the news and for all the wrong reasons. It has been the unnecessary third .....

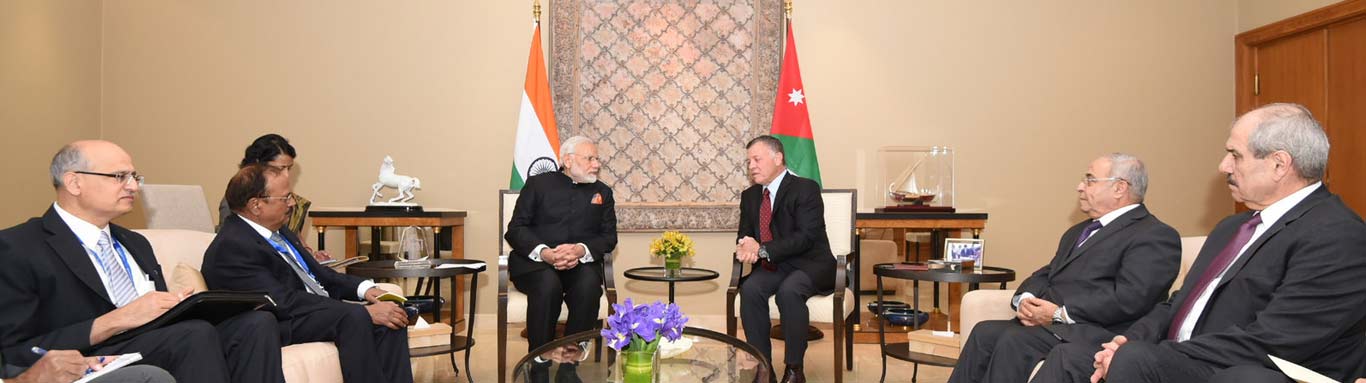

During the close to a century of its existence, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has been, as former .....

In their eagerness to focus on and flag the de-hyphenation of the traditional Israel-Palestinian bin.....

In the closely scrutinised India-Israel relationship, there is little in the public domain that rema.....

You know what, it will go to the dustbin’ my articulate friend was blunt, brutal but.....

Balfour Declaration, A Century Later If one were to make a list of the most influential.....

Professor Bernard Lewis—a towering personality on the Middle Eastern academic landscape—.....

B orn in Poland on 2 August 1923, Szymon Persk who later Hebraised his name as Shimon Peres was the leader.....

W hat What began as a protest by a marginalized vegetable vendor in Sidi Bouzid in Tunisia soon spread lik.....