Breaking

- MENU

Book review of Squaring the circle: Mahatma Gandhi and the Jewish Homeland. By Professor P. R. Kumaraswamy, New Delhi: Knowledge World Publisher, 2017. pp.234. ISBN: 978-3-87324-06-0

No doubt the Arab–Israeli conflict has dominated the horizon of global politics and international diplomacy for decades. It is possible to claim that the sympathy or antipathy to the cause of Palestine has become a litmus test for political ideology, political correctness, political wisdom and political pragmatism for many nations, and the same stands true for India.

When it comes to deciphering or defining India’s association with the cause of Palestine or its relationship with Israel, Mahatma Gandhi’s words from 1938 in Harijan still serve as a guide for many: “Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English and France to the French”.

In this context, professor P. R. Kumaraswamy, an authority on Israel in India, made a pioneering effort not only to decipher and decode the meaning of Gandhi’s statement but in his latest book, “Squring the circle: Mahatma Gandhi and the Jewish Homeland” has conducted an empirical reading of the political, religious, cultural, and strategic constraints or motivations which led Gandhi to make his aforementioned remarks. These words have always been understood as ardent disapproval of Zionism and a sign of unending love for Palestine.

Since the centrality of the book is Gandhi’s position towards the idea of a Jewish homeland, before digging deep into the political, religious and strategic factors shaping Gandhi’s insensitivity towards the issue, the author travels into Gandhi’s African years (1893-1914) and identifies his Jewish companions who might have left some imprint on his earlier notion of Judaism and later Zionism. The author traces his earlier acquaintance with Judaism in Africa to his two prominent companions: Mr. Kallenbach (a wealthy man) and Mr. Henry Solomon Leon Polak (a journalist). Mr. Kallenbach was Gandhi’s “alter ego” and was the owner of Tolstoy Farm established by Gandhi (p. 55). Gandhi addressed him as “my dear lower house and Mr. Kallenbach in turn reciprocated by addressing Gandhi as his “upper house (p.56).

Mr. Kallenbach later became a zionist when they both met again in 1937 in India after 23 years. Mr. Kallenbach was influenced by Gandhi who dissuaded him from going to Palestine. In the book, the author blames these two early companions for Gandhi’s disenchantment with the political cause of Jews because they were non-practicing and had limited knowledge of Jewish religion which deprived Gandhi of accumulating substantial knowledge about Jews and Judaism.

Unlike Mr. Kallenbach Mr. Henry Solomon Leon Polak was more of a disciple than a friend and it was through Polak that the Indian nationalist leaders came to know about Gandhi’s activities and accomplishments in South Africa. Mr. Polak visited India twice in 1909 and in 1911 and met many prominent leaders of congress. There were other Jews too in Gandhi’s surroundings, namely Mr. A. E. Shohet and Ms. Sonja Schlesin the first had published a rebuttal to Gandhi’s November 1938 article and the second had served as Gandhi’s secretary in South Africa.

The issue of Palestine had gripped the political consciousness of Indian leaders amidst the freedom movement. In order to prevent any links between Indian Muslims and Palestine, zionist leaders made five separate attempts to persuade Gandhi to make a statement in favor of their cause.

The primary hypothesis of the book is to explain the political constraints and oversensitivity towards the religious minority, again for political gains, which shaped Gandhi’s position towards the Jewish homeland. The demonstration of political constraints or ideational selectivity is well reflected in Gandhi’s overarching involvement in the Khilafat movement in an endeavor to win the hearts of the Muslims. According to the author, Gandhi’s rhetoric for the cause of Palestine is further driven by growing Muslim League (ML)-Congress political warfare to sway the Muslims by acting more loyal to Palestine than the Palestinians themselves. In that sense, the book attributes Gandhi’s position to a lack of knowledge about Judaism, the taboo of zionism, and urging the Jews to practice non-violence. This is how the author concludes that Gandhi’s antipathy to the zionist cause was not woven by his ethical or moral fabric of his political ideas but was more determined by his narrow political vision.

Gandhi, according to the book, was swayed by the Palestinian cause as an Islamic one under the influence of the Khilafat Muslim leadership. Gandhi acting as an astute politician recognized the gravity of the Khilafat for Indian Muslims and in March 1920 observed, “Khilafat is a question of life and death. (p. 79). The book then continues by claiming that the Balfour declaration of 1917 had further annoyed the Muslims and Gandhi took it as an additional opportunity to galvanize the Hindu-Muslim unity which consequently blinded him to a significant reality and deprived him of analytical clarity about the Jews (p. 169).

If Gandhi’s views on Jewish nationalism in the 1920s were hostage to the Khilafat movement, so his views in 1930s were detrimental to growing Muslim League-Congress ideological warfare coloring Gandhi’s vision on zionism. It was then only power-politics which overshadowed Gandhi’s thoughts on Judaism according to the author, and it was not driven by his moralist or ethical stance as perceived by many.

Both camps had joined a new political turf to woo the Muslims either to prove their secular credentials or to emerge as the sole voice of Muslims by Congress and ML respectively. Gandhi’s grave concerns for Hindu-Muslim unity and protecting the secular credentials would have suffered in case of any overt inclination towards the Jews or Zionism. Palestine had become the most dominant issue in foreign policy agenda of the Congress and contextualization of Palestine as an Islamic issue was a domestic compulsion for Gandhi (p. 130 and 158) Many of the Zionist-Congress meetings (including with Nehru and Gandhi) that came to an end with the Harijan article of 1938, were kept secret fearing the backlash from the Muslims as Palestine and Zionism had became a site for ideological contestation between the ML and the Congress.

According to the author, it was not merely the politics of Khilafat or ML-Congress rivalry but his unfamiliarity with Judaism and the enigma of zionism that deterred Gandhi from exhibiting any sympathy to the Jewish homeland. In other words, Gandhi failed to capture the link between the historic Jewish suffering with the zionist demand for a homeland (p. 163). For Gandhi, Palestine was a “Biblical conception (p. 161) but he deprived the Jews of the same claim and rejected the religious claim of zionism to Palestine (p. 162). So for the author, Gandhi’s opposition to religious-based claims over Palestine was exclusively directed at Jews and not at the Muslims. If for Nehru Palestine was an imperialist issue, for Gandhi it was a mix of religion and imperialism.

While talking about Palestine, Gandhi, like many others, could not overcome the long-held skepticism about zionism. No doubt, after 1938 there were many changes in Gandhi vis-a-vis the Jewish cause but he never saw zionism as an answer to the Jewish plight (p. 160). Gandhi was never ready to see Jews as more than followers of a particular faith. Gandhi praised zionism as a “lofty aspiration” in its “spiritual” term but declared that if it meant the reoccupation of Palestine, zionism has no attraction for him. (p. 147). This was his anti-zionist conviction.

Among the long list of the author’s grievances against Gandhi, his ignorance about the plight of the Jews in Europe and his demand for Jews to practice non-violence while overlooking the violence of others have captured the attention of the author in particular. Gandhi’s advocacy for non-violence was indicative of his complete unfamiliarity with the unfolding carnage in Hitler’s Europe. Gandhi’s ignorance is further enforced when he asked the German Jews to resist their deportation (p. 182) and further his parallelism between Churchill and Hitler is another sign of his ignorance.

Gandhi continued to call for moral victory against Hitler despite all sort of subjugation being carried out against the Jews. Amidst the ongoing pogroms against the Jews, Gandhi continued to criticize them for seeking help form the US and the UK.

Gandhi had declared himself a Muslim, a Parsi, a Christian and a Jew (p. 17) but it is too difficult to evaluate the impact of these religions on his political thought. Among many factors, the author attributes Gandhi’s lack of sympathy for zionism to his little knowledge of Judaism but is it necessary that knowledge of a particular religion should lead one to support any political project emanating from that religion? In India Maulana Azad was an astute Islamic scholar but vehemently opposed the idea of Pakistan, an Islamic cause for the ML. There was nothing wrong if Gandhi could not see Jews beyond the people of a particular faith and perhaps anticipated the grave outcome of the religio-political project of zionism. One can also not deny the fact about Gandhi’s acquaintance with Ben Gurion’s links to terror groups, actively involved in displacing the indigenous population, which would have determined and shaped the views of Gandhi about zionism and the early leadership of Israel.

Gandhi was not infallible nor did he ever claim to be so. One can also accept that Gandhi did not have sufficient knowledge of Judaism, but his position towards zionism was not driven by domestic political influence as alleged by the author but it was more due to his preoccupation with the freedom struggles.

Perhaps the author has not done justice to Gandhi by reducing everything to the politics (Khilafat and ML-Congress rivalry), ignoring his lifelong moralist and ethical principles.

Gandhi’s anti-imperialist philosophy and his political righteousness cannot be undermined by branding him an hypocrite, a man with double standards or a Muslim as alleged by the author while the fact remains that Gandhi was above religion and race. It was not merely ML-Congress tussle to exhibit more loyalty to the cause of Palestine but rather it was a position reflective of India’s anti-Imperialist ethos and support for national causes in Asia and Africa which guided India‘s erstwhile stance and one can see that in India‘s involvement in the anti-imperialist movement in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

Ignoring all that undermines the anti-imperialist ethos of the Indian freedom struggle and the core of India’s foreign policy in the evolving years. There were other sentiments also which had shaped India’s stance towards Palestine. India has its own civilizational strength and political understanding which might have guided both leaders: Nehru and Gandhi.

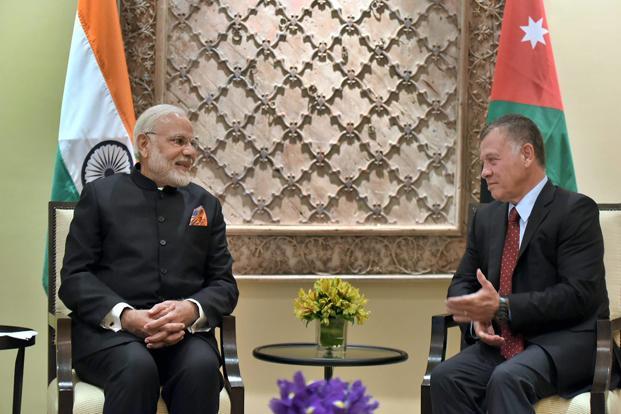

Moreover the growing proximity of India towards the state of Israel and the deepening military and strategic engagement between the two in recent years has proven that India’s foreign policy never remained faithful to the ideal or dictate of one individual. India had come a long way to recast its foreign policy and its world view with the changing time.

Nonetheless, this volume is unique in many ways and undoubtedly will trigger a new sensitivity and fresh debate among scholars and strategic community who have traditionally remained faithful to Gandhi’s dictum of 1938 when it comes to defining India-Israel relations. What further distinguishes the collection are the many revelations such as by Pyarelal (confidant of Gandhi) about hiding some statements or views of Gandhi from public knowledge to avoid controversy which is rarely known.

The book provides a sea of information on various aspects of India-Israel evolving ties which perhaps only an archive could have provided. It is a huge research work and no doubt through this book, Gandhi has been revisited and rediscovered. In India it is the season for rediscovering Gandhi, and everyone from politicians to intellectuals are doing it in their own way.

This article was first published in Open Democracy on 20 January 2018 and has been reproduced with the permission of the Author

__________________________________________________________________________________________

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

Dr. Fazzur Rahman Siddiqui is Middle East political analyst and currently associated with a Delhi-based foreign policy think tank. He has earned his PhD in Middle Eastern studies and his core research area is Middle East political issues, regional politics and political Islam.Recently he has published a book ," Political Islam and the Arab Uprising : Islamist Politics in changing time. , published from Sage , 2017. He writes regularly on political and social issue in the Arab world and earlier he was with the Ford foundation. he can be contacted on fazzur@gmail.com/Tweeter- fazzurrahman@

Much of what Israel and the Palestinians are experiencing today has befallen them under Netanyahu&rs.....

Lurking in the background of a Saudi-Moroccan spat over World Cup hosting rights and the Gulf crisis.....

Any protracted conflict can come to an end under certain circumstances that either evolve over a per.....

Amid ever closer cooperation with Saudi Arabia, Israel’s military appears to be adopting the k.....

Mounting anger and discontent is simmering across the Arab world much like it did in the w.....

Argentina’s cancellation of a friendly against Israel because of Israeli attempts to exploit t.....

Dear M. Haniyeh and Sinwar; I am writing this letter to you in the wake of the latest confrontati.....

The Civil War in Syria has ravaged the country, took the life of nearly 500,000 people and has force.....

India’s prospective engagement with the Arab world, especially the six-member Gulf Cooperation.....

President Trump’s characterization of the US attack on specific Syrian chemical storage and re.....

Debilitating hostility between Saudi Arabia and Iran is about lots of things, not least who will hav.....

Saudi Arabia, in an indication that it is serious about shaving off the sharp edges of its Sunni Mus.....

The United States has been and remains the staunchest supporter of Israel, and its unqualified suppo.....

Prominent US constitutional lawyer and scholar Alan M. Dershowitz raised eyebrows when he described .....

.jpg)

The geopolitical developments in the Middle East over the past fifteen years have created .....

I was in Israel when Trump made his announcement recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s c.....

Iran is back in the news and for all the wrong reasons. It has been the unnecessary third .....

During the close to a century of its existence, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has been, as former .....

The Student and Faculty Committee (SFC) of the Centre for West Asian Studies, School of Internationa.....

In the closely scrutinised India-Israel relationship, there is little in the public domain that rema.....

You know what, it will go to the dustbin’ my articulate friend was blunt, brutal but.....

Balfour Declaration, A Century Later If one were to make a list of the most influential.....

18th Turkish Parliamentary Elections, October 1991[*] Political Parties .....

Gulshan Dietl, India and the Global Game of Gas Pipelines, (New York and London, Routledge.....

SQUARING THE CIRCLE: MAHATMA GANDHI AND THE JEWISH NATIONAL HOME Author: P R Kumaraswamy Knowl.....

B orn in Poland on 2 August 1923, Szymon Persk who later Hebraised his name as Shimon Peres was the leader.....

I. George W. Bush and Israel II. From the Inauguration to 9/11 III. From 9/11 to Ju.....