Breaking

- MENU

The maiden visit by Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, which aimed to strengthen the bilateral relations, largely remained a ceremonial affair. Since 2018, the relations have been in limbo, characterized mainly through limited cooperation and paltry trade of non-oil commodities. During his two-day visit, the top Iranian diplomat called upon Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar, and National Security Advisor Ajit Doval. In addition to political leadership, the Iranian Minister held meetings with business people and religious leaders in Mumbai and Hyderabad.

Interestingly, the visit took place at a time when both countries were reeling through diplomatic crises of their own. For Iran, the nuclear diplomacy has witnessed sudden deterioration with the chided resolution passed during the Board of Governor meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that carped Iran for its failure to adhere to its obligations under its NPT-mandated “Safeguards Agreement.” Before the vote, Tehran made pre-emptive responses by shutting down two of IAEA’s monitoring devices on its nuclear sites and starting the installation of advanced IR-6 centrifuges at the Natanz nuclear facility. Meanwhile, New Delhi has had a tough week handling the fallout of remarks by a functionary of the ruling BJP party that affronted Prophet Mohammad. India was pushed into a defensive position on the diplomatic front, particularly in the Middle Eastern countries, including Iran.

In such a context, the visit by the top Iranian diplomat was expected to fetch a diplomatic win; instead, it turned out to be a lackluster affair. However, it was not the Foreign Minister or the Indian hosts that were to blame, but the problem lies with the flawed approach to bilateral ties that the visit highlighted. Both in diplomatic discourse and academia, there is a tendency to exaggerate the bilateral ties while failing to follow up on the promises and commitments. Another mistake here is overlooking the limitations of the relationship. Here, four observations can be made to understand why the bilateral ties remain stagnated and why the visit by the Minister did little to remedy it.

First, the high-level visits have a limited impact on the actual comportment of relations. Although Amir-Abdollahian’s visit was the first major visit by the Iranian side since the hardliner government of Ebrahim Raisi came to power in June 2021, the Indian side has been actively engaging the Raisi administration from day one. Indian External Affairs Minister (EAM) Jaishankar was the first foreign dignitary to meet President-elect Raisi, which followed his attendance at the swearing-in ceremony a month later. After that, various telephonic conversations and side-meetings at multilateral forums have taken place. Yet, nothing substantive has come out of these engagements. Indeed, the Minister’s visit carried several expectations, particularly on expanding trade relations, but nothing major came out of the visit except the signing of the Mutual Legal Assistance treaty.

Second, despite lengthy talks about increasing trade of non-oil commodities, there was no upscaling of trade, although the countries were presented with opportunities. For instance, the crisis in Sri Lanka has left a large void in the market for orthodox tea, which is popular in Iran. India is one of the largest producers of orthodox tea (after Sri Lanka), and therefore, it carries considerable scope to ship this particular variety of tea to Iran. This links to the broader discussion of diversifying the trade basket; thus far, no mechanisms have been prepared in this regard. The sanctions are frequently miscreant, yet despite numerous talks about developing an alternative mechanism to trade, nothing has been done. Last month, Ali Chegeni, the Iranian Ambassador to India, informed the media about efforts to “diversify our channels of payments” under the Rupee-Rial’ mechanism to facilitate trade. However, the issue has not been fully chased through as one sees no mention of such initiatives on the agenda.

The investment dimension of bilateral relations also suffers from similar concerns, particularly with the problem of over commitment. The Chabahar project is a prime example in this regard. Although functional, the port continues to suffer from underutilization and hitherto yielded a fraction of what is being promised either in Afghanistan, Central Asia, or even the ambitious International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC). In 2021, the decision of the Iranian government to go ahead with the construction of the ‘Chabahar-Zahedan Railway Project without India was another illustration.Although both sides insist that India has not been dropped from the project and can join it at any point in the future, there is little evidence to support such claims.

The Press Releases provide excellent insights into how the two countries treat their bilateral ties, not only through mention but also through omission. There were earlier talks of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the two countries (as they had before the Revolution), but no such points were raised during the visit. The mentioned FTA would be consequential since the two countries do not provide preferred access to goods and services as Iran is not a WTO member.

Third, the Indo-Iranian relations are hostage to third parties. From the Iranian side, the US is a persistent factor in its comportment of ties with India. Readily, the Indian vote against Iran at the IAEA’s Board of Governor meeting is referenced by the Iranian side to fault India. In fact, the assertions have been made that India must support Iran in defying the sanctions against Iran, which in all fairness, is a big ask. What’s more, despite the insistence from both sides to strengthen relations, neither India has a specific regional policy targeting Iran (since Iran forms part of the PAI (Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran) Division at MEA), nor does Iran distinguish India as part of its “Look East” policy that has mainly included China, and lately, Russia.

Conversely, there is an overt emphasis on the Indian side to view Iran from the prism of a third country. The Indian efforts to outmanoeuvre Beijing’s influence in Iran (and Pakistan) are critical determinants in New Delhi’s engagement with Iran. Although the fundamental equation has changed, Afghanistan is still a good example to understand India’s calculus in Iran. The Press Release on the visit highlighted the trilateral cooperation (between India, Iran, and Afghanistan) in the health sector, wherein India has provided COVID-19 vaccines to Afghan refugees in Iran. Although such multilateralism is laudable, the visit could have also strived to boost cooperation in the health sector between the two countries, especially after Ali Chegeni hinted at it last month. Yet, no MoUs on health were on the agenda during the visit.

Fourth, invoking the Kashmir issue over the last few years by the Iranian side has contributed negatively to the Indo-Iran relationship. Such remarks carry the potential to turn retaliatory very rapidly. The Iranian comments on Indian sensitivities have coincided with a rough patch in bilateral ties. And lest the Iranian side refrains from commenting on Kashmir and the internal affairs of India, the chances are that India may resort to pushing back by commenting on human rights issues in Iran or the government crackdown on demonstrators. In such context, the amicable addressing of the issue of remarks against the Prophet is a step forward in the right direction. Iranian side noted that it was an “arbitrary act” that should be avoided in the future.

Finally, if the bilateral relations have to be advanced, there is an urgent need to walk the talk from both sides. This would first necessitate recognizing where the nations view each other in their priority list. Indeed, the visit was a good marker for showing commitment to bilateral ties, but the commitments need to be backed by actions. And the actions should follow a meaningful approach to bilateral relations where the two countries must first recognize each other’s priorities and realities.

Note: This article was originally published in Financial Express on 10 June 2022 and has been reproduced with the permission of the author. Web Link

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

Prabhat Jawla has a Master’s degree in international relations from South Asian University, New Delhi. His areas of interest include geopolitics in West Asia with a particular focus on IRGC, Iran’s domestic and foreign policies and Indo-Iraq relations. He had worked as a research intern in West Asia Centre at Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA) and he tweets at @aprabhatjawla.

Iran celebrated another year of victory of the ‘1979 Revolution’. However, the country-w.....

Following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (also Zhina), widespread protests have gripped the Is.....

At the dawn of a new century in the Persian calendar, the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khame.....

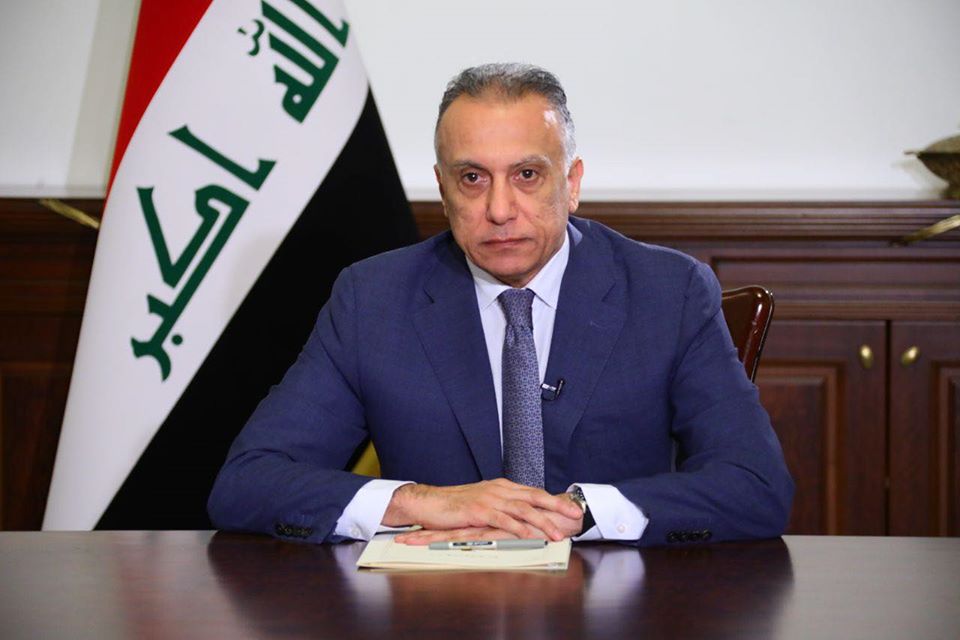

In May 2020, after months of political wrangling, the Iraqi Parliament (Council of Representatives) .....