Breaking

- MENU

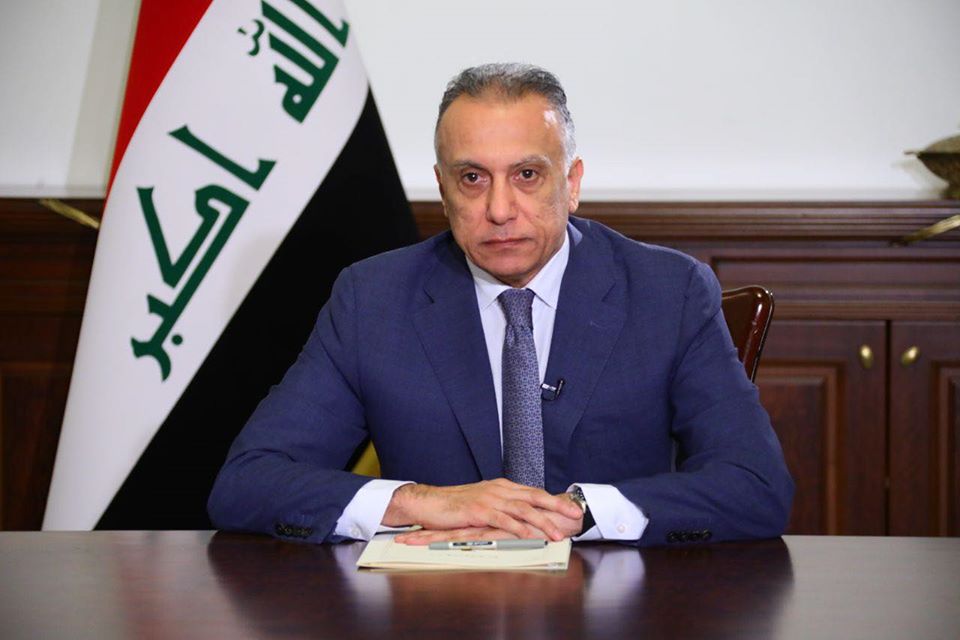

In May 2020, after months of political wrangling, the Iraqi Parliament (Council of Representatives) approved the Government of Mustafa Al Kadhimi, who had been heading the Iraqi National Intelligence Service (INIS) since 2016. Ever since assuming office, Kadhimi has wrestled with various sets of political, economic and foreign policy challenges. The most fascinating of these challenges has been Kadhimi’s management of Iraq-Iran relations in the light of worsening Iran-US relations. His prime ministership seems to have taken a more assertive approach with regards to Iran, where rather than confronting Iran directly, Kadhimi has chosen to slowly curb its influence within Iraq.

After being declared as the Prime Minister-designate in March, Kadhimi faced scathing opposition from the Fatah Alliance, which is majorly composed of Shia groups close to Iran. These groups alleged his closeness to Washington as a major impediment in supporting him. Even though the Shia coalition came around, but Kadhimi has faced long-drawn criticism of his policies being anti-Iranian and pro-US.

A key aspect of Kadhimi’s approach that has differed from his precursors has been his position on foreign intervention in various Iraqi institutions, particularly in Iraq’s security structure. In his writings in the Al-Monitor, he had expressed strong views about depoliticizing the Popular Mobilisation Front (PMF)—an umbrella organisation of militias, which was constituted by a fatwa by Ayatollah Sistani in June 2014. Major militias under PMF are Badr Organization, Asa’ibAhl al-Haq (AAH), Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH), Kata'ib Sayyid al-Shuhada, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba, among others. In general, the heads of these militias have had a strong affinity with Iran, primarily because they were exiled in Iran after the Eight-Years War (1981-88), which enables Iran’s strong influence within Iraq.

The PMF established a decentralized militia that operates under the office of the Prime Minister, but most of the planning and operational aspects stay with the chairman of the PMF and his deputy, which renders PMF out of the chain of command. Usually, these two positions have been held by individuals closer to Tehran. Earlier, this year, the head of the PMF, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis was killed alongside Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commander Qassem Soleimani in a US drone strike, After Muhandis, Abu Fadak al-Mohammadawi replaced him, who is also close to Tehran. Soon after his appointment as the head of the PMF was announced, the Iranian-linked social media accounts started circulating the pictures of Fadak with Soleimani, where Soleimani is seen kissing his forehead, a respected gesture within the culture.

Since he came to office, Kadhimi has pursued an assertive policy against the PMF, which aims to demobilize the organization by assimilating it under the Iraqi Armed Forces. Such outspoken attempts have led to confrontation between PMF and the Prime Minister's Office. The critics of PMF argue that it had fulfilled its mandate of fighting the Islamic State; therefore, it is no longer needed. They also cite the irregularities and mismanagement of their funds that include salaries, offices and benefits, which are concerning given that such funds (about $2 billion annually) are provided from the state budget, which is already under severe strain owing to the economic crisis.

Additionally, he had made significant changes in Iraq’s security structure, his domain for the last four years. Kadhimi reinstated Lieutenant General Abdul Wahab al-Saadi as the Chief of the Iraqi Counterterrorism Agency, who had faced criticism under the Mahdi government, who later sacked him. Other appointments into crucial offices include Qasim al-Araji as National Security Advisor, replacing Faleh al-Fayadh– a prominent figure within the PMF, assigning General Abdul-Ghani al-Asadi as the head of national security agency and appointments to multiple other positions. Such a change in leadership of the PMF is an attempt to curb the Iranian influence, without confronting Tehran directly.

Yet another instance of such behaviour was when the Iranian energy minister was visiting Iraq in August, the timing of which coincided with the Second US-Iraq Strategic Dialogue. During this visit, the Iranian delegation included Ismail Ghani, the IRGC commander who succeeded Soleimani. His entry into Iraq was made conditional on obtaining a prior visa, which was a stark change under Kadhimi’s predecessors, who never dared to put such conditions on Soleimani.

As soon as the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was relaxed, Kadhimi declared Riyadh as his first destination for a foreign visit. This came as a shock for the groups closer to Iran. Though the trip was eventually cancelled owing to King Salman's health, Kadhimi made his first visit to Tehran as the Prime Minister, his decision in this regard reflecting his cold approach towards Iran. Further, in May 2020, during a visit by Iraq’s finance minister, a deal was finalized with Riyadh that provided $3 billion to Iraq to meet its budgetary requirements. Additionally, Riyadh will make investments in the Iraqi natural gas sector. Iran-backed groups criticized such a move.

Unlike his predecessors who chose to pursue a policy of status quo, Kadhimi has taken a more assertive tone against Iran. However, instead of confronting Iran directly, it has primarily targeted Iran’s influence within Iraq. He has been able to strike a delicate balance between Iraqi interests, without upsetting Iraq's relations with Iran. In moving ahead, the extensive Iranian influence within Iraq is likely to continue under Kadhimi’s term; however, the minor incremental changes that he has adopted hold the potential for change in Iraqi politics. In other words, it is difficult at present to assess how much change Kadhimi's rule will bring to Iraq, as well as its relations with Iran, but his term marks a change from the past.

Note: This article was originally published in Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, West Asia Watch Vol 3, Issue 3, July-September 2020 and has been reproduced under arrangement. Web Link

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

Prabhat Jawla is an Assistant Professor in the Centre for Political Science in Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

The 12-day war between Iran and Israel last June marked a consequential flashpoint for the geopoliti.....

Iran celebrated another year of victory of the ‘1979 Revolution’. However, the country-w.....

The maiden visit by Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, which aimed to strengthen the.....

Following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (also Zhina), widespread protests have gripped the Is.....

At the dawn of a new century in the Persian calendar, the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khame.....