Breaking

- MENU

The coming to power of the AKP is one of the defining moments in the history of modern Turkey. Here was a party committed to its Islamic and Ottoman roots, yet pledged to “modern” ideas of democracy and freedom. Importantly, it was able to come to power through democratic means, despite Turkey’s chequered history of democratisation. The immediate political divisions and fractious politics of Turkey, with the withering away of the secular–liberal–nationalist coalition of the Demokratik Sol Parti (DSP, Democratic Left Party), ANAP and MHP that had governed the country since 1997, along with the poor management of a severe economic crisis facilitated AKP’s win in the elections. People were looking for a party that could govern well. The AKP mayors, particularly in Istanbul, had provided better administration during those trying times. Moreover, the memories of 1997, when Erbakan’s government was forced out, and of 1999, when Erdogan was jailed for reciting a poem, were fresh in peoples’ mind. The sympathy was with the AKP and the newly formed centre-right moderate Islamist party capitalised on that.

Notwithstanding the immediate factors, the coming to power of the AKP was hailed as one of the key markers of democratisation. Despite the detractors of the AKP not being convinced, the larger public opinion, both within Turkey and outside, was appreciative of the political developments. During the first two terms of its rule, the AKP was able to deliver on the promises of strengthening democracy, enhancing the rule of law and expanding the rights and freedom enjoyed by the people, by introducing new laws and constitutional amendments and by promoting social inclusiveness. Moreover, the AKP government worked on ending the military’s influence in politics. These were no small achievements given the historical evolution of Turkey. During this period, the AKP government did not indulge in electoral manipulation, adopted a conciliatory approach towards opposition and did not push any agenda that was non-consensual.

Gradually, however, the situation started to unravel. It would be wrong to put the entire blame on the AKP which constantly saw itself being pushed to the wall, despite back-to-back electoral victories, by those it thought were representing the interests of the “deep state” and entrenched elites. This led to a situation where the AKP started to hit back using the government machinery to isolate, marginalise and coerce those it identified as the enemy of the people and the state and opposed to the AKP continuing in power, thereby creating a politics of friction, division and polarisation. The AKP and its leadership used all their power to strike at those who were creating dissent against its rule.

What ensued in the process was a democratic slide and concentration of power in the hands of a few through constitutional amendments and redefining of the public sphere. This resulted in the revival of an authoritarian state system whereby any form of dissent was being muzzled, and even silenced, in the name of national interest. Formally, this process of creating an authoritarian state structure was completed through the April 2017 constitutional amendment that changed the system of government from a parliamentary form to presidential one. The amendment package significantly weakened the judicial and legislative checks on the executive and reduced the accountability of the executive to the legislature.

This process of formalisation of an authoritarian state structure is the leading challenge for democratisation in Turkey. The politics of change pursued by the AKP government has created a new normal in Turkish politics. It has led to a situation where the dissenting voices have been silenced, rule of law weakened and political divide sharpened, reminiscent of the older days of authoritarian governments. Another aspect of AKP’s politics has been the marginalisation of the military from politics. This is significant development, especially given the political history of modern Turkey in which the military has played a crucial role in the foundation and stability of the republic, as well as maintaining its secular credentials. The challenge going forward is to find a balance between non-intervention of armed forces in politics and non-humiliation of soldiers by the political class. What ensued during and in the aftermath of the July 2016 coup attempt shows that the military has the potential to try and intervene in politics. At the same time, the farcical trials and public humiliation of soldiers can reignite public opinion favourable to the role of armed forces in politics.

The other challenge for democratisation is the creation of a hegemonic public sphere by the AKP. The AKP, through coercion and co-option, has been able to redefine the Turkish public sphere into one that allows the expression of only pro-government opinion. The AKP has fallen into the same trap which it had promised to challenge when it had first come to power. The inability to give shape to a democratic public sphere is one of the major failures of the AKP government and going forward, this is an important challenge for democratisation. Nonetheless, there are signs, such as the Gezi Park protests and the 2019 municipal election results, which underline that all is not lost as far as public sphere is concerned and that the opposition in Turkey has been able to create a counter to the hegemonic public sphere created by the AKP.

Challenges

There are, thus, three challenges for democratisation in Turkey: (i) authoritarian state structure controlled by Erdogan; (ii) maintaining the changed dynamics of civil–military relations; and (iii) upending the hegemonic public sphere created by the AKP.

Authoritarian Political Structure

As discussed in the earlier chapters, the AKP, using the electoral politics, political polarisation and constitutional reforms, has been able to establish an authoritarian political structure with President Erdogan at the helm. This is not an unprecedented situation for Turkey, but the test for the polity and its democratic roots will be in altering this authoritarian state structure without descending into chaos or ensuing large-scale political violence. This cannot be achieved without creating a consensus for return to a democratic system, free from any autocratic tendencies, and evolving strong checks and balance for future governments. This will need a cross-section of ideologies, including liberal nationalists, Kurds and moderate Islamists, to come together to challenge Erdogan’s stranglehold on power. Given the current political dynamics, this looks like an improbable scenario. However, political alignments and realignment cannot be ruled out and that is an encouraging sign.

Civil–Military Relations

As visible during the failed coup attempt in July 2016, despite the complete reorientation of civil–military relations during the AKP’s rule with subordination of the military to the elected government, the tendency of the soldiers to think of themselves as the guardians of Turkish state and national politics is not dead. The civil–military relations are of profound importance for democratisation and the ability of the AKP to send the military back to the barracks is a major achievement. However, if the AKP continues to take the country on the path of democratic slide, the possibility of the military to strike back cannot be completely overruled. This means that for the future of democracy, it is important that the nature of civil–military relations achieved during the AKP government is maintained and no scope for military’s intervention in politics is allowed. This can only be achieved based on evolving a politics of consensus and not through military coups.

Hegemonic Public Sphere

The AKP has been able to create a hegemonic public sphere to silence all voices of dissent and marginalise all non-AKP public opinion. This is one of the biggest challenges for democratisation and though there are signs of revival of a more pluralistic public sphere, it will not be an easy task to reverse the current trend of hegemonic public sphere created under Erdogan’s watch. It will require creating a counter-narrative to AKP’s narrative of going back to Islamic and Ottoman roots. The current liberal secularist voices, to a large extent, have been delegitimised in the larger public opinion because of their support to elements that advocate marginalisation of Turkish history in public sphere. It would require a reinvention of liberalism and secularism within the context of Turkish political history.

Turkey is at a critical juncture in its history. Though the AKP’s rule, at least in the early stages, strengthened aspects of democratisation, in recent years it has created a major challenge through the authoritarian rule of President Erdogan. This poses a serious dilemma for Turkey in near future, and how the Turkish polity and the electorate reacts to the entrenchment of AKP’s power politics will decide the fate of the polity. It can lead to perpetuation of the one-man rule or this can be challenged through electoral politics and by pursuing politics which are not divisive and not based on hatred. The examples on the way forward can be taken from Turkish history itself, which is full of incidents that either perpetuated the authoritarian governments and pushed Turkey towards democratic slide or helped strengthen values that paved the way for democratisation and consensus-based politics.

Note: This an excerpt from Erdogan’s Turkey: Politics, Populism and Democratisation Dilemma published by Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses in July 2020 and has been reproduced with the permission of the author. Web Link

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

Md. Muddassir Quamar is an Associate Fellow in Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. He holds a Ph.D. in Middle East studies from Jawaharlal Nehru University and his doctoral thesis focused on social dynamics in Saudi Arabia in the context of the tensions between two seemingly non-harmonious trends; Islamization and modernization. He has a broader interest in Gulf societies, political Islam, Middle East geopolitics and India’s relations with the Middle East. He has co-authored two books India’s Saudi Policy: Bridge to the Gulf (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) and Persian Gulf 2019: India’s Relations with the Region (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). He is currently working on a manuscript on education reforms in Saudi Arabia. He has co-edited four anthologies, including Changing Security Paradigm in West Asia: Regional and International Responses (Knowledge World, 2020), Political Violence in MENA (Knowledge World, 2020), Islamic Movements in the Middle East: Ideologies, Practices and Political Participation (Knowledge World, 2019) and Contemporary Persian Gulf: Essays in Honour of Gulshan Dietl, Girijesh Pant and Prakash C. Jain (Knowledge World, 2015). His research papers have appeared in leading international journals such as Asian Affairs, Strategic Analysis, India Quarterly, Contemporary Arab Affairs, Digest of Middle East Studies, Journal of Arabian Studies and Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. As part of his project in MP-IDSA, Dr. Quamar authored a monograph on Erdogan’s Turkey: Politics, Populism and Democratisation Dilemmas. Since 2018, he has served as the Book Review Editor for Strategic Analysis, the flagship journal of MP-IDSA published in association with Taylor & Francis. In May 2020, he edited an MEI Monograph Middle East Fights Covid-19: A Fact Sheet with contributions from students pursuing Masters in IR in JNU. He regularly contributes Op-Ed articles on developments in the Persian Gulf, Middle East and India’s relations with the region for Indian and international forums. In 2014-15, he was a Visiting Fellow at the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, Riyadh. Dr. Quamar has been associated with the Middle East Institute, New Delhi, in various capacities since its foundation and serves as Associate Editor of its flagship journal, the Contemporary Review of the Middle East published by Sage, India.

On January 17, 2022, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) was rocked by two attacks after drone attacks ta.....

Within a span of just over a year since the announcement of the Abraham Accords, between Israel and .....

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar’s visit to Israel signifies the burgeoning Indo-Israel.....

On 28 August 2021, Iraq hosted the first “Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership&r.....

Recent developments in Afghanistan–the US military withdrawal and return of Taliban– has.....

The Taliban takeover of Afghanistan has wider ramifications for the world. Among the key questions t.....

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar attended the swearing-in ceremony of the new Iranian preside.....

The revitalisation of ties with Iran will remain confined to the immediate issue of shared interests.....

Israel and Hamas have engaged in fighting each other since 2006 when Hamas emerged victorious in the.....

Tensions have gripped the Eastern Mediterranean (East Med) for the past few months owning to differe.....

Qatar is an important country in the Gulf with which India has traditionally had strong bilateral ti.....

International geopolitical developments and the growing chances of friction between the global power.....

In recent years, Turkey’s foreign policy has attracted scrutiny because of its aggressive post.....

India and the United Arab Emirates share a vision for peace and prosperity. Under the leadership of .....

Though the news of China and Iran entering into US$400 billion agreement and Iran going ahead with C.....

India’s relationship with the Gulf has witnessed a qualitative transformation since the August.....

The results of country-wide municipal elections in Turkey held on 31 March 2019 threw a few surprise.....

Like other parts of the world, West Asia (or the Middle East) too is hit hard by the spread of COVID.....

Iraq is suffering from internal divisions and external interventions for long. The problems of the p.....

The West Asia is one of the most volatile and conflict-ridden regions in the world today. Given the .....

In the Persian Gulf, the New Year began with a bang. On January 3, the world woke up to the news of .....

Major General Qassem Soleimani, commander of the elite Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.....

For over two months, youth in Iraq are protesting against corruption, unemployment and Iranian and A.....

The historic relations between India and the Gulf countries have undergone a qualitative transformat.....

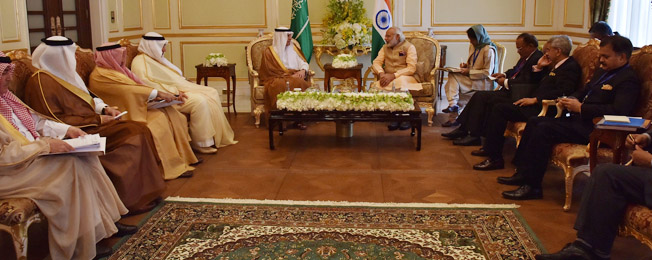

India and Saudi Arabia enjoy traditional friendly ties. Both are strategic partners and are working .....

Prime Minister Narendra Modi undertook a visit to the UAE and Bahrain over the weekend. This was his.....

The 16th Ministerial meeting of the Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) took place in Doha this week. Th.....

India’s relationship with the Gulf has witnessed a qualitative transformation since the A.....

On March 24, 2019, the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) announced the capture of Baghouz, a .....

The visit of Saudi Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Adel al-Jubeir to New Delhi; close on the h.....

India and Saudi Arabia have increased defence and security cooperation in the fields of combating te.....

Economic and social reforms have emerged as the focus area in Saudi Arabia under the leadership of K.....

The US and Turkey are back on collision course over the Kurdish question in northern Syria. The late.....

The Civil War in Syria has ravaged the country, took the life of nearly 500,000 people and has force.....